Cairnduff & Carnduff Web Site.

.

|

Thomas Carnduff The Belfast Poet. |

|

|

Thomas Carnduff FamilyTree |

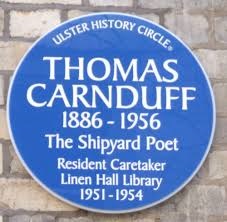

Thomas Carnduff ‘The Shipyard Poet’ |

Thomas was born in 13 Kensington Street, off Sandy Row, Belfast, on 30 January 1886 |

Thomas Carnduff was born in 13 Kensington Street, off Sandy Row, Belfast, on 30 January 1886, His parents were, James Graham Carnduff an army Corporal and Jane Bollard, his second wife.Thomas the youngest of 7 children,and had a half brother and sister He spent his early childhood in Dublin, where he was educated at the Royal Hibernian School and the Royal Military College. He worked as a butcher's boy, in a thread and needle factory, in a printing house, as a drover in a linen factory, and in the Belfast shipyards.

While working in the Belfast Steam Print Company from 1906 to 1914 he revelled in the camaraderie of his well-versed, articulate co-workers. He read widely in order to contribute to their stimulating levels of daily debate on the social issues of the time. In 1914 he started work as a plater's helper at Workman, Clarke and Co.He joined the Young Citizens' Volunteers and in 1916 enlisted in the Royal Engineers, serving at Ypres and Messines.

On leaving the army in 1919 he was re-employed at Workman's, remaining there until the firm was wound up in 1935. It was hard, dangerous work, which often involved working at heights - the fear of which Carnduff never entirely overcame. Accidents were a daily occurrence in the yard, and on one occasion he was taken to hospital after suffering injuries from a heavy spanner which had been dropped from 40 feet. Carnduff was involved in the Labour and trade union movements and active in the Independent Orange Order. He was a friend of Peadar O'Donnell and supported the Connolly Association |

The Orangeman's Handshake. Written by Billy Mitchell |

Peadar O'Donnell |

|

|

He had just recovered his strength after enduring forty-one days on hunger strike and was confident of an early release from prison. However, he still believed that he had a duty to try to escape. And so, with some help from friendly guards, slipped out of the Curragh Prison Camp and started out for his beloved Donegal.

O'Donnell chose a rather long and circuitous route home. Stowing away on a boat for Liverpool, he then boarded a second boat for Belfast before catching a train to Londonderry and then walking over the mountains to his home in West Donegal. When his boat docked at Belfast the veteran republican was met by Thomas Carnduff, Master of Sandy Row Independent Orange Lodge. "This is the one time that an Orangeman's handshake is better than a papal blessing", remarked O' Donnell. Not that O'Donnell was ever in line for a papal blessing. The only pronouncements likely to come O'Donnell's way from the Catholic hierarchy at the time would have been denunciations rather than blessings.

Thomas Carnduff and Peadar O'Donnell were political enemies. Indeed, when we consider that Carnduff was a RUC Reservist and O'Donnell was a member of the anti-treaty IRA, it could be said that they were military enemies as well. Yet for all their enmity, O'Donnell and Carnduff were kindred spirits. Both were writer's who used their literary skills to depict the harsh realities of life in their respective home environments.

O'Donnell, the republican and socialist, wrote with passion about the struggle for survival endured by the people of West Donegal against the ravages of poverty, civil conflict and nature. Carnduff, the Protestant who regarded himself as both an Irishman and an Orangeman, wrote with equal passion about the concerns of Belfast's working classes as well as about culture and politics.

While O'Donnell's contribution to Irish literature has been well documented and applauded, the writings of Carnduff have largely been neglected. A self-taught manual worker, Carnduff wrote about a dozen plays for both radio and theatre as well as several books of poetry and numerous essays. His play "Workers" received rapturous applause when staged at Dublin's Abbey Theatre in 1932, yet the same play was abandoned in his native Belfast when the Opera House objected to its working class ethos. As Sarah Ferris has pointed out, by 1970 the literary reputation of Thomas Carnduff "had sunk without trace"

O'Donnell's reputation as a writer has been adequately recognised, yet his reputation as a republican and a socialist has been dismissed as irrelevant by all but a handful of republicans who steadfastly refuse to equate republicanism with Catholic Nationalism or Green Toryism. The Donegal Democrat, which owed its establishment to the advice given by O'Donnell to three print workers during a labour dispute in 1918, concluded that O'Donnell was merely an agitator "who never achieved anything good for his country".That is something else the two writers had in common, they were prophets without honour amongst their own people.

Carnduff, the Belfast Orangeman, was a regular visitor to the home of the O'Donnell's in Dublin. During one of these visits he presented the veteran republican with his Orange Sash. O'Donnell promptly placed this in a glass case and exhibited it with pride to all who entered his abode. Political differences they may have had, but O'Donnell had no problem with Carnduff's "orange feet" crossing the threshold of his home; nor did he find the Sandy Row mans Orange regalia to be a source of offence. Men and women of integrity are not easily offended by the beliefs, emblems and culture of their opponents.

Before he died O'Donnell made arrangements with Belfast republican, Jack Mulvenna, to ensure that the Sash was returned to Carnduff's family. In 1991, some five years after O'Donnell's death, the Sunday News carried a report of the Sash being handed over by Mulvenna to Carnduff's sons

The friendship between O'Donnell and Carnduff reminds us that political adversaries need not dehumanise one another. On the contrary, they should have the capacity to respect each others political integrity and dedication to a cause. It reminds us too that those who have worn the uniform of opposing forces need not live in a state of perpetual hatred, base recrimination and ongoing demonisation. As in the case of Carnduff and O'Donnell, dedicated political opponents are very often kindred spirits who share similar passions and, but for an accident of birth, could have been on "the same side".

Writing from a loyalist perspective, I am saddened by the fact that working class Protestants such as Thomas Carnduff have been relegated to the margins of politics, culture and literature. Misunderstood by those of us who for so long swallowed the bitter pill of anti-Catholic sectarianism, and rejected by others whose bitter anti-Protestant sectarianism refused to acknowledge that anything good could be said or be written by an Orangeman, Carnduff has much to say to us today as we prepare to write an obituary for the Good Friday Agreement

"...am I to blame if [my ancestors] looked on the land with approval and stayed"? (Thomas Carnduff, 'I have faith in Ireland')

All his life he had written poetry, and in 1936 he formed the Young Ulster Literary Society and was a member of the Irish Pen Club.He wrote for several newspapers, including the Bell and published books of poems,His poetry is collected as Songs from the Shipyard and other Poems (Belfast, E.H. Thornton, 1924); and Song of an Out of Work (Belfast, Quota Press, 1932). These volumes were posthumously republished as Poverty Street and Other Poems (Belfast, Lapwing Press, 1993). He wrote many plays for radio.: The First Warrant (1930); Workers (Dublin, The Abbey Theatre, 1932) he succumbed to an unholy joy as he, an unemployed shipyard man, became a playwright. Belfast's Ulster Theatre had previously rehearsed but abandoned the play when the Opera House objected to its working-class tendencies. Machinery (The Abbey Theatre, 1933);Traitors (Belfast, The Empire Theatre, 1934); Castlereagh (The Empire Theatre,1935); Birth of a Giant (1937); The Stars Foretell (1938) and Murder at Stranmillis. The Birth of a Giant was a play written for radio. His later years were spent working as a caretaker in the Linen Hall Library, where his portrait now hangs.

In all, Carnduff wrote more than a dozen plays, including radio drama. He published two books of poetry, and was a prolific essayist on Ulster drama, Ulster workingmen poets, and Belfast's politics and cultures. In l936, he founded the Young Ulster Society. These achievements were extraordinary in a context widely dismissed as a cultural desert. Yet, by l970 when five extracts of Carnduff's unpublished autobiography surfaced in the Linen Hall Library, Belfast, his reputation had almost sunk without trace. Twenty-four years passed before his edited autobiography was published in John Gray, ed., Carnduff: Life & Writings, Belfast: Lagan (l994).

A founding member of Belfast P.E.N.,. Carnduff's manuscript plays and other material, including Carnduff's diary correspondence, Letters to Mary, remain unpublished.He worked at a variety of jobs, at the Belfast shipyards and elsewhere, and also served as a sapper in the Royal Engineers during the First World War. He later served in the Ulster Special Constabulary. an Independent Orangeman, a poet, a dramatist, and a prolific essayist on local cultural politics. Observing of his home city that, "tragedy simply cried out from the streets for expression", he uniquely rejected stage Irish dialogue and farce to voice the realist accents and desperate concerns of its working people. Carnduff was painfully aware that regarding Belfast's educational institutions he remained a looker-on from the outside all his life. Carnduff successfully launched plays such as Castlereagh and Traitors in the home city that constantly exasperated him, but of which he never tired.Thomas Carnduff died on 17 April 1956 leaving behind a legacy of exceptional writing and social commentary. He had used his writings to highlight the plight of the under-privileged and to inspire them to realise their higher potential. He strove to demonstrate that the working classes merited a valued place in modern society. He is buried in Carnmoney Old Cemetery, Co. Antrim.

|

My Ancestry lies buried under the shadow of an ancient round tower within the grounds of Drumbo Presbyterian Meeting house "Thomas Carnduff,Belfast" c1938.

He was named afrer his Grandfather Thomas Carnduff who was born in 1810 in Ballyauglis Drumbo, and died 1882. Thomas`s father James Graham Carnduff was an army Corporal and Jane Bollard, his second wife.Thomas the youngest of 7 children,and had a half brother and sister He spent his early childhood in Dublin, where he was educated at the Royal Hibernian School and the Royal Military College. He worked as a butcher's boy, in a thread and needle factory, in a printing house, as a drover in a linen factory, and in the Belfast shipyards.

While working in the Belfast Steam Print Company from 1906 to 1914 he revelled in the camaraderie of his well-versed, articulate co-workers. He read widely in order to contribute to their stimulating levels of daily debate on the social issues of the time. In 1914 he started work as a plater's helper at Workman, Clarke and Co.He joined the Young Citizens' Volunteers and in 1916 enlisted in the Royal Engineers, serving at Ypres and Messines.

On leaving the army in 1919 he was re-employed at Workman's, remaining there until the firm was wound up in 1935. It was hard, dangerous work, which often involved working at heights - the fear of which Carnduff never entirely overcame. Accidents were a daily occurrence in the yard, and on one occasion he was taken to hospital after suffering injuries from a heavy spanner which had been dropped from 40 feet. Carnduff was involved in the Labour and trade union movements and active in the Independent Orange Order. He was a friend of Peadar O'Donnell and supported the Connolly Association

born 1844 in Drumbo Co Down. He was an army

nd Jane Bollard, his second wife.Thomas the youngest of 7 children,and had a half brother and sister He spent his early childhood in Dublin, where he was educated at the Royal Hibernian School and the Royal Military College. He worked as a butcher's boy, in a thread and needle factory, in a printing house, as a drover in a linen factory, and in the Belfast shipyards.

While working in the Belfast Steam Print Company from 1906 to 1914 he revelled in the camaraderie of his well-versed, articulate co-workers. He read widely in order to contribute to their stimulating levels of daily debate on the social issues of the time. In 1914 he started work as a plater's helper at Workman, Clarke and Co.He joined the Young Citizens' Volunteers and in 1916 enlisted in the Royal Engineers, serving at Ypres and Messines.

On leaving the army in 1919 he was re-employed at Workman's, remaining there until the firm was wound up in 1935. It was hard, dangerous work, which often involved working at heights - the fear of which Carnduff never entirely overcame. Accidents were a daily occurrence in the yard, and on one occasion he was taken to hospital after suffering injuries from a heavy spanner which had been dropped from 40 feet. Carnduff was involved in the Labour and trade union movements and active in the Independent Orange Order. He was a friend of Peadar O'Donnell and supported the Connolly Association |

|

Noel Carnduff on his search for his father's papers. |

Titanic Belfast |

Circular tiling in the centre of the ground floor with a quote from Thomas Carnduff. |

Songs from the Shipyards: |

O city of sound and motion!... |

...O city of endless stir! |

From the dawn of the misty morning... |

...To the fall of the evening air. |

From the night of moving shadows... |

...To the sound of the shipyard horn. |

We hail thee Queen of the Northland... |

...We who are Belfast born. |

He was named after his grandfather Thomas Carnduff who was born in 1810 in Ballyauglis Drumbo, and died 1882. Thomas's father James Graham Carnduff was born 1844 in Drumbo Co Down. He was an army Corporal who married twice, his second wife Jane Bollard born abt 1855 was Thomas's mother she married James in Kildare Ireland on 30 September 1871, they had 7 children.. James first wife was Mary Melville they married on 9 august 1867 in Aldershot England and had 2 children.

"My ancestry lies buried under the shadow of an ancient round tower within the grounds of Drumbo Presbyterian Meeting house"Thomas Carnduff,"Belfast" c.1938

|

|

|

Visitors to the Linen Hall Library,Belfast, in the 1950s probably paid scant attention to the resident caretaker – an elderly figure who quietly went about his duties. Few, apart from the literary fraternity, would have recognised Thomas Carnduff, better known as the ‘Shipyard Poet’ or sometimes the ‘People’s Poet’.

In his lifetime, his prolific outpouring of poetry, plays and contemporary prose reflected a passion for the city of his birth and a social reformer’s zeal to advance the economic and social status of its working-class citizens.

Carnduff, himself of solid working-class stock, was born in Kensington Street, Sandy Row, in 1886. From 1906 – 14 he worked as an assistant in the stereotyping section of the Belfast Steam Print Company, where he revelled in the camaraderie of his well-versed, articulate co-workers. He read widely in order to contribute to their stimulating levels of daily debate on the social issues of the time.

In 1916 he enlisted in the Royal Engineers and served at Ypres and Messines. On demob from the army in 1919, he was re-employed at Workmans as a plater’s helper at a rate of twenty-one shillings (£1.05) for a fifty-four hour week – working from 6 a.m. to 5.30 p.m every day.

It was arduous, dangerous labour, which often involved working at heights – the fear of which Carnduff never entirely overcame in his long shipbuilding career. Accidents were a daily occurrence in the yard, and on one occasion, Carnduff was taken to hospital after suffering injuries from a heavy spanner dropped from 40 feet.

As a youth Carnduff had written poetry – experimenting with what he called ‘doggerel’ – and during his early days in the shipyard he was inspired to write about his experiences there. A collection of writings, called Songs from the Shipyard and other Poems, was published in 1924 and dedicated to, ‘My comrades of the shipyards and of the days and nights toil we spent together’.

The book, funded by a sympathetic relative, captured the rich vein of social and human activity in which he now played a part but, unfortunately, it did not sell well – it was a huge disappointment to Carnduff and his sponsor.

|

|

|

|

The Yard Playwrights

Tom Thompson on how the Belfast shipyards informed the work of Thomas Carnduff, Sam Thompson and Wilson John Haire.

Occasional poems and articles in Belfast and Dublin newspapers earned pittances, and did little to relieve the hardships of feeding and supporting his family of six. After a brief foray into self-employment, typing plays, sermons and poetry for others, he was encouraged by Ulster writer Richard Rowley to write a play. Choosing to write about his experiences in the shipyards, Carnduff produced Workers. Several attempts to have the play performed locally were unsuccessful, but in 1932 it opened at Dublin’s Abbey Theatre. Carnduff recalled his anticipation of the performance. ‘The pleasure of seeing one’s efforts in a public theatre, and one with an international fame, when the author is an unemployed shipyard man, is an episode incapable of recording'.Following the success of the Dublin premiere, Workers played at the Empire Theatre, Belfast, to equally enthusiastic audiences. The applause of Carnduff’s former workmates packing the ‘gods’ was music to his ears.

In 1935 he was laid off for the last time from Workman Clark when the shipyard went bankrupt and closed. But the success of Workers had led to commissions for plays and poetry, as well as invitations to lecture on drama and social issues. He would go on to write plays such as Machinery, Traitors and Castlereagh, deriving inspiration from his on-off working days in Workman Clark’s shipyard, and the history and environment of a much-loved Belfast. |

Thomas Carnduff died on 16 April 1956, but he left behind a legacy of exceptional writing and social commentary. He had used his writings to highlight the plight of the under-privileged and to inspire them to realise their higher potential. He strove to demonstrate that the working classes merited a valued place in modern society.

On 26 January 1960, in a struggling Belfast theatre, a bomb shell of a play was performed – one that would shatter for all time the cosy, elitist world of serious Ulster drama. The performance ran for six weeks to full houses, and was a huge success for its author and producers.

The play, Over the Bridge, by Harland & Wolff painter Sam Thompson, raised profound questions about religious tensions and prejudices within Northern Ireland society and, in tackling such a taboo subject, it challenged local theatrical tradition, which tended to steer clear of such controversial matters.

Over the Bridge was based on shipyard incidents of the 1930s and was performed during the ongoing IRA campaign of 1956 – 61. For some, Thompson’s play was an overdue exposure of sectarian prejudices against Catholics; others disagreed vehemently. Many were also shocked by the coarseness of the dialogue and the passion exhibited in public, albeit on a stage. If the author had intended to stimulate discussion about Ulster political attitudes, he certainly achieved his objectives, and more.

Sam Thompson, born in 1916, was the seventh in a family of eight children, born and raised in Montrose Street, off Newtownards Road, Belfast. His father, a lamplighter with the City Corporation, eked out his meagre wages with a part-time sexton’s job at the nearby St Clement’s Church.

When Sam entered Harland & Wolff in 1932 as apprentice painter, he was concerned that, like his brother, he would be sacked as soon as he served his time. At the time shipbuilding nationwide was at its lowest ebb – there were few orders, empty slipways and thousands out of work.

He became a member of the Painter’s Union, and eventually a shop steward, and there he found a platform where he could campaign for social reform. Regular meetings of interested workers took place in the shipyard toilets to debate the urgent issues of the day and to discuss possible means of resolving them.

His first tentative steps into the theatrical world were inspired by friendships made at that [the Elbow Room pub] and he was soon obtaining minor acting and directing roles with the Rosemary Players and other amateur societies. Other acting parts in the Group Theatre followed.

After an encounter with Sam Hanna Bell, a progressive BBC producer, Thompson began writing for radio, producing shows such as A Brush in Hand, about an apprentice shipyard painter, a documentary, Tommy Baxter, Shop Steward, and a weekly serial, The Fairmans.

Apart from his now busy writing career, Thompson was volubly promoting the ideals of socialism and had become an active member of the Northern Ireland Labour Party (NILP) which, in the mid-1950s, was beginning to make serious inroads into the traditional Belfast Unionist vote.

Paddy Devlin, an NILP member and later founder member of the SDLP, described a meeting he had with Thompson. ‘I liked him instantly. He was an uncomplicated straight shooter who always appeared to be smouldering on the edge of explosion into flames at the sight and sound of injustice. Everyone within earshot knew where Sam stood on every issue. If they did not, it never took Sam long to tell them.’

Thompson meanwhile, ever the ardent socialist, had ambitions of more substantial writing than documentaries or stories for radio audiences – he had an overwhelming desire to expose some of the sectarianism he had seen or heard about in the shipyard.

In 1958, after two years of intensive writing, he completed what became his seminal, dramatic work, Over the Bridge. The ‘bridge’ in question was a matter of debate. Was it the Queen’s Bridge over the Lagan, or Fraser Street Bridge, off Newtownards Road, which led directly into the shipyard?

At the time, actor James Ellis was artistic director of the Group Theatre, Belfast. He was always keen to promote fresh local writing talent, so when Sam Thompson approached him with the challenge, ‘I’ve got a play you wouldn’t touch with a barge pole,’ Ellis was intrigued. He took on the challenge, knowing that the play would be controversial.

However, two weeks before the public performance, the Group’s board Chairman, Ritchie McKee, requested substantial cuts to the script. He informed the Belfast Telegraph: ‘The play is full of grossly vicious phrases and situations which would offend every section of the public. It is the policy of the Ulster Group Theatre to keep political and religious controversies off our stage.’

Ellis and Thompson refused to meet McKee’s request to cut the text, and they, along with other prominent Group actors, resigned. They formed their own theatre group, Ulster Bridge Productions and eventually found an alternative venue. The Empire Theatre in Belfast was spacious and opulent, and was a high-risk, expensive venue to launch a controversial drama. But the confidence of Ellis and Thompson was vindicated.

Over the Bridge, played with a well-known Ulster cast (including Thompson in a minor role), was a resounding overnight success. Audiences of forty-two thousand attended its six-week run – a record for a play performed in Belfast. The profitable Belfast premiere was followed by performances in Dublin, Glasgow, Edinburgh and Brighton.

The success of Over the Bridge launched Thompson into a relentless, bruising writing routine, and three other plays followed. The Evangelist, about the nineteenth-century religious revival in Ireland, was successfully played in the Opera House, Belfast, in 1963.

Cemented with Love, which had a theme of political corruption, was intended for broadcast in 1964, but was postponed due to a pending election. It was eventually performed in May 1965. Sadly, Thompson did not see it. He had died on 15 February 1965 from a heart attack. His last play, Masquerade, still in draft stage and set in London, was never completed or performed.

Sam Thompson’s passing at the early age of forty-nine was a serious loss to Ulster’s theatrical society as well as to Belfast’s close-knit socialist fraternity, which was in need of popular figures to promote its cause.

Wilson John Haire’s early background, neither urban nor industrial, was vastly different to the other shipyard writers. He was born in 1932 on the Shankill Road, Belfast. His mother, a Roman Catholic, came from a landowning family in Omagh, County Tyrone, while his father, a Presbyterian, was a tradesman joiner. When Haire was still young, his family moved to Carryduff, County Down – a rural setting that was still a reasonable distance from Belfast, where most available jobs were located.

Haire’s recorded memories of early life in Carryduff are vague – his writings take the format of biographical fiction. But it does appear that, despite the difficult economic climate of the 1930s, hardship was not a feature of life in the Haire family, although poverty was widespread in their local community.

Wilson, against his parents’ wishes, left school at fourteen years of age to obtain a job as office boy at Harland & Wolff. The transition from a rural way of life to the heavily industrialised world of shipbuilding must have been an emotional and cultural shock for young Haire.

Two years later, he paid his five pounds deposit – a hefty sum in those days – and became an indentured apprentice joiner. He was a colleague of mine in the Joiners’ Shop and his memories of that period – when fact and fiction can be separated – are recorded in his book, The Yard, which describes a way of working life now long gone.

On completion of his five-year apprenticeship in the cavernous Joiners’ Shop – in which his father had also worked during the war years when it was used for building Stirling bomber fuselages – Haire became restless. He wanted a change from the constraints of his family life and his work routine.

He had just begun to earn full wages as a tradesman, but he handed in his board for the last time and resigned from Harland & Wolff, despite having no other job to go to. It was a typically impetuous act which undoubtedly earned his parents disapproval.

At only twenty-two years of age, he became impatient for change and fresh challenges once again. As a trained joiner – at a time when a joiner, especially a shipyard one, was considered to be one of the elite, and more skilled than a regular carpenter – Haire had no difficulty obtaining a carpenter’s job in London. Around 1960, after several years in London, a disposition towards and latent talent for writing began to emerge.

Three stories, ‘Refuge from the Tickman’, ‘The Beg’, and ‘The Screening’ were published in the Irish Democrat, a London weekly newspaper. A subsequent foray into drama writing produced two one-act plays – The Clockwork Orange, centred around a controversial Belfast protest by the Reverend Ian Paisley; and Divil Era, about the B-Specials – both of which were performed and well-received at Hampstead Theatre, London.

Although he lived for a relatively short time in his native Ulster, his early writings are coloured by a Catholic perspective, and most of his dramatic output was inspired by the political and religious complexities of life in Northern Ireland. In his later career – as indicated by plays such as Lost Worlds, performed at the Academy of Dramatic Art, London, in 1984 – he has moved away from exploring Ulster’s political themes, and instead covers the wider global arena of social justice.

He has received drama awards from various British arts councils and theatres, and in 1974, the London Evening Standard acclaimed him as ‘the most outstanding playwright’. In recognition of his commercial and artistic success, he became resident dramatist at the Royal Court Theatre, London. A year later, he spent a brief period in Belfast as resident dramatist at the Lyric.

Regrettably his national (and, later, international) recognition as a serious playwright has not been matched by similar acclaim in his native country, where he remains largely unknown. Though this may be partly his own fault. Unlike Thomas Carnduff and Sam Thompson, who unashamedly displayed a passion and affection for their birthplace, Haire’s works seem to portray only the negative aspects of his homeland, and, since he left Northern Ireland for good, there has been little evidence of any deep affinity or affection for it.

The above is an abridged version of 'The Yard Playwrights', a chapter from Tom Thompson's book Auld Hands: The Men Who Made Belfast's Shipyards Great, which is out now, published by Blackstaff Press.

|

Thomas

Carnduff: 1886-1956 Biographical Chronology by Sarah Ferris appointed Literary

Executor to the Carnduff Papers.

Website: www.sarahferris.co.uk

| 1810 |

Carnduff’s grandfather, Thomas

Carnduff, born Ballyauglis, Drumbo. Co. Antrim. |

| 1844 |

Carnduff’s father, James Graham Carnduff born. |

| 1860 |

The Carnduff family move to

Sandy Row. |

| 1871 |

James Graham Carnduff married Jane Bollard on September 30 at the Parish Church,

Great Connell, Kildare. |

| l872 |

Arthur Carnduff born. |

| l874 |

Martha Carnduff born. |

| l880 |

Rose Carnduff born. |

| l882 |

Carnduff’s grandfather, Thomas

Carnduff, dies. |

| l886 |

Thomas Carnduff born at l3

Kensington Street, Belfast. |

| 1896 |

April 30: Carnduff became a

pupil at the Royal Hibernian Military School. |

| 1900 |

Jan 23 Leaves Royal

Hibernian Military School and begins work in a

local printing firm and on to various jobs as

butcher’s delivery boy, light porter, factory

hand, and catch-boy in the shipyard |

| 1901 |

James Graham Carnduff dies. |

| 1906 |

Starts as an assistant in the

stereotyping department of the Belfast Steam-Print

Company, Belfast (incorporating The Ulster Echo and The Witness). |

| 1909 |

August 20: marries Susan

McCleery McMeekin on August 20 at Great Victoria

Street Presbyterian Church. |

| 1911 |

September 29: James Graham

Carnduff born. |

| 1912 |

September 28: signs ‘Ulster’s

Solemn League and Covenant’ at the City Hall,

Belfast. |

| 1912 |

October 12: attends the ‘first

Official Drill’ of the Cliftonville Company of the

Young Citizen Volunteers at Cliftonville

Presbyterian Church, Belfast. |

| 1914 |

July 1: Joseph Carnduff born. February 5: leaves the Belfast

Steam-Print Company to work as a plater’s helper

at Engine Works, Workman, Clark & Co. Ltd., |

| 1916 |

Joins the Royal Engineers.

Served at Ypres and Dunkirk. October 1: Thomas Noel Carnduff born. |

| 1918 |

Demobbed. Went first on ‘the dole’, then back to

the shipyard. 1921 |

| 1922 |

February 21 to December 31, l925: Special

Constable, Ulster Special Constabulary, North

West Brigade, 1st West Battalion. |

| 1924 |

October 20: Samuel McMeekin

Carnduff born. Songs from the shipyard and other poems

published by E. H. Thornton. |

| 1929 |

Politics performed by the

Stanhope Players. |

| 1930 |

The First Warrant, a play in two acts. The Haunted House and Revolt in Ballyduff performed by York Street Non-Subscribing

Presbyterian Church Dramatic Society. |

| 1932 |

Workers opens at the Abbey Theatre. Song of an Out-of-Work published by

Quota Press. Possibly, Shipyardmen,

a play for radio set in l932. |

| 1933 |

Machinery opens at the Abbey

Theatre. |

| 1934 |

Traitors opens at the Empire Theatre, Belfast. Noel

Carnduff’s role as ‘a Belfast newsboy’, was

created specially for him by his father. |

| 1935 |

Castlereagh opens at the

Empire Theatre. Laid off from the shipyard. Unemployed for

a several years before securing a job as a bin man

at the Belfast Corporation. |

| 1936 |

Possibly, Death Keeps No

Calendar, set in l936,

and Curfew (or Derry). July: A Dustman’s Life broadcast by BBC. November: With Jack Hayward and Denis

Ireland formed the Young Ulster Society at a

meeting held in the YMCA. |

| 1937 |

December: Birth of a giant broadcast by BBC. Murder at the New Road broadcast by Radio

Éireann. |

| 1938 |

The Stars Foretell read at a

Young Ulster Society meeting. Edited the first issue of Young Ulster. Pantomime, Bluebeard, performed by the

Harold Norway Theatre Company in the Ulster Hall. June: Catchboy broadcast on BBC Radio. |

| 1939 |

March 17: Susan Carnduff dies September: transferred from the Belfast

Corporation to the A.R.P. Rescue Service as a

telephonist. Continued as a Civil Defence

Volunteer until December Industry broadcast by the BBC. Possibly,War Brides. l943, then transferred to the

Administrative Staff as a Caretaker. (Awarded a

Defence Medal in l946). Recorded ‘Northern Ireland contribution to

Christmas Day Empire exchange, l939’ for the BBC. |

| l940 |

Begins his “Journal to Mary”. |

| 1942 |

Working on his Autobiography;

by October Richard Rowley was editing a typescript

for the printed version which never materialised. May 15: secretly married Photographer’s

Assistant Mary McElroy at All Souls’ Presbyterian

Church,Belfast. December: as a founder member of the Belfast

P.E.N. Carnduff (with Mary) attends a formal

Dinner of the International P.E.N. in Dublin.

Other committee members were Richard Hayward, John

Hewitt, Roy McFadden,Ruddick

Millar and May Morton. |

| 1946 |

Transferred from Civil Defence

to Belfast Corporation Surveyor’s Department as

yardman. |

| 1951 |

Retired from Belfast

Corporation; became resident caretaker at the

Linen Hall Library. 1954.Cahill & Company of Dublin advance Carnduff

£25 for his autobiography; again it never

appeared. |

| 1956 |

April 17: Thomas Carnduff dies. He is

buried at Carnmoney Old Cemetery, Co. Antrim. May:

Rev. A.L. Agnew, “Obituary, Mr. Thomas Carnduff”,

Calender, All Souls’ Second Presbyterian Church. Belfast. |

| 1970 |

Five extracts from Carnduff’s

autobiography surfaced in the Linen Hall Library. |

| l978 |

John Gray, Librarian of the

Linen Hall, introduced three chapters,

“Adolescence”, “Industry” and “Drama” in “Thomas

Carnduff, l886-l956 : chapters from an unpublished autobiography”, Irish Booklore,

Vol. 4, No.1, pp. 24-46. |

| 1986 |

Noel Carnduff returns to

Belfast and begins searching for his father’s

missing works. In “Thomas Carnduff” in the Linen Hall

Review, Vol. 3, No. 3, (Autumn l986), p.18, John

Gray Press

interest prompted Rosario Player, Jack O’Malley,to donate the play Death keeps no calender to the

Linen Hall Library.acknowledged Noel’s role in

recovering three more chapters of the

autobiography, “On the dole”, “Culture in

Belfast”, and “The last chapter”. |

| 1988 |

Noel Carnduff presents

Carnduff’s portrait to the Linen Hall Library. |

| 1990 |

January 23: Mary Carnduff dies;

Carnduff papers held by her pass to Noel. |

| 1991 |

March 25 to April 26: The Linen

Hall Library stage an exhibition of the “Life and

Work of Thomas Carnduff”. Noel receives Give losers leave to talk and

an extract of a pantomime, Bluebeard. |

| |

March 24: The Tinderbox Theatre Company produce

“The Writings of Thomas Carnduff” at the Old

Museum Arts Centre. April: Noel Carnduff presents

Carnduff’s typewriter to the Ulster Museum. Denis

Smyth edits Poet of the people : |

| |

Anon., “Thomas Carnduff

l886-l956 : Poet of the People: his life, times

and his writings”, appeared in a dockside literary

magazine Waterfront published by North Belfast

History Workshop. |

| |

Anon., “Thomas Carnduff: Poet

of the People”, Lurigethan, Journal of North

Belfast History Workshop, No. 2, (Spring/Summer

cl991), ed. Denis Smyth. |

| 1996 |

Sarah Ferris begins cataloguing

Carnduff’s papers. |

| 1999 |

January 20. Carnduff’s papers

are catalogued in The Thomas

Carnduff Archive. At Noel Carnduff’s request, the

papers are lodged in Queen’s University Library.© Sarah Ferris |

|

|

15 Jan 2018 |

.For non-commercial private study and research only |

Copyright © 2021 Cairnduff |

|